Philosophers throughout history have sought to understand what constitutes a good life. Two candidates often rise above the others: happiness and meaning.

Happiness can be understood in many different ways. Psychologists have recently taken interest in the philosophical debates on the difference between hedonia and eudaimonia, that are often understood as two different conceptions of happiness. Eudaimonia is often thought to be closely linked to meaning, purpose and values, whereas hedonia is more like an experience of enjoyment and satisfaction and absence of unpleasant emotions and experiences (for example, Huta and Waterman, 2014).

As Huta and Waterman (2014) clarified, “According to the classical understanding of eudaimonia, the term was not intended to refer to a subjective state but to what was worth pursuing in life.” In that sense, it resembles what many existentialists consider the questions about meaning. Yet, they consider eudaimonic experiences to be strongly positive, which might distinguish the concept from meaning (see previous blog on positive and negative experiences).

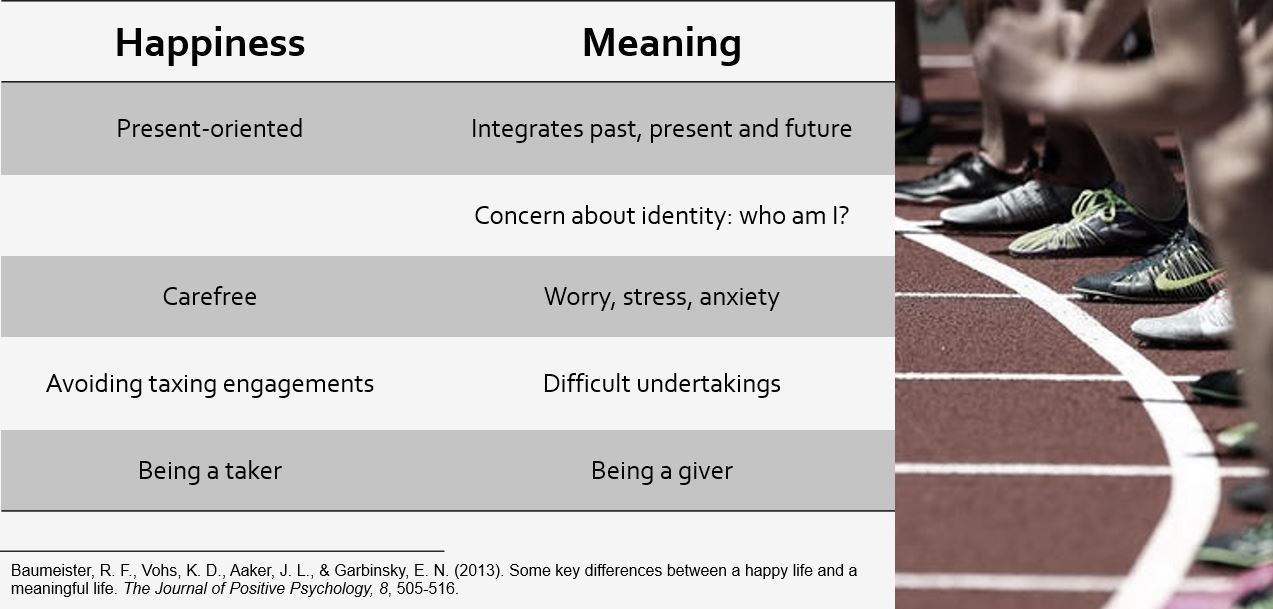

As I have previously mentioned in the blog, social psychologist Roy Baumeister and his colleagues have shown that happiness (considered in the hedonic sense) and meaning are partly different versions of “a good life”. There are some things that bring us both happiness and meaning, but there are also things that contribute to happiness but not meaning, and vice versa.

Sport and exercise are often promoted to people because of health benefits. Interestingly, Baumeister et al. (2013) showed that health plays an important role in terms of happiness, but is irrelevant for meaning. As they noted, ‘Healthy and sick people can have equally meaningful lives, but the healthy people are happier than sick ones’.

If exercise is promoted because it produces health benefits (as is most often the case in exercise recommendations), the goal seems to be ultimately to increase people’s happiness (even if it is not directly stated).

Some interesting differences between (hedonic) happiness and meaning include temporal orientation (short vs long), types of activities, emotional valence, and being a taker vs a giver.

It becomes intriguing to ask which version of the good life might be more readily available through sport activities.

A quick answer would be that both can be available. We hear about many positive experiences and moments of enjoyment in sport. Flow states, runner’s high, being in the zone, having fun, and so forth. There are certainly moments of happiness in sport.

But: Many of these things become accessible through long-term dedicated practice. Runner’s high is more readily available if you are in good shape. That means, you’ve probably done a lot of running before and between these experiences, and most likely also had days when it wasn’t fantastic. Try to run through a Finnish winter and you’ll get the point.

Looking at the list of characteristics of meaning in Baumeister’s study, we see that quite a few are relevant to sport. Why are sport psychologists talking so much about anxiety and stress in athletes? Because sport is often stressful! Why is not everyone a high level athlete? Because it is difficult and requires long-term commitment. Why do we have over 100 studies on athletic identity in sport psychology? Because it does seem to be important, both for elite and non-elite participants.

Danish sport sociologist Henning Eichberg argued that sport is a means to make our lives more difficult than it needs to be. Running a marathon is a difficult and often unpleasant task, and a completely unnecessary one. Trying to squat with 100kg is difficult (at least for many of us), and also unnecessary. If meaningful life is often characterized by difficult undertakings, sport is one candidate for such undertakings.

If we ultimately strive for happiness and meaning, there is a case to be made that we engage in sport at least partly because it brings us meaning.

But does sport provide a false sense of purpose and a way of escaping the absurdity of existence and meaningless world, as Prof John Kaag suggested? We will hopefully find this out in the Meaningful Sport podcast soon. Thanks, @ImSporticus for making the link! 🙂