In the forthcoming ISSP conference, we’re doing a talk with Michael McDougall on ‘Lessons Learned from Meaningful Work: Implications for Sport Psychology and Understanding Meaningfulness in Sport’ . After recording the presentation a few days ago, I wanted to reflect on a few things arising from this work.

Meaning and meaningfulness in sport (broadly understood) and physical education has been a topic of (often philosophical) writings already for decades, but it seems that as a research community we have recently made more efforts to study it empirically. As we are making these steps, we felt that it would be valuable to draw some insights from a research area – that is, meaningful work – where much more efforts have been put on studying these concepts.

And so, for ISSP, we wanted to review what we know about meaningful work and what could be learned from that. Of course, some discussions are needed on whether work and sport are similar or different (some of which we included in another paper). In our ‘lessons learned’, we included broad themes that we argue are applicable to sport context as well.

And so, let’s get to those lessons then.

#1: Conceptual efforts are critically important when moving our work in a sport context forward. In Meaningful Work literature, Bailey et al. (2018) uncovered 28 different measurement scales. Sometimes meaning and meaningfulness are used interchangeably, sometimes they are differentiated. And often the theoretical underpinning was not clearly articulated, but meaningfulness appeared as akin to a motivational attitude or perception. Especially since there are hundreds of studies on motivation for sport and PA, it will be important to work out how these concepts overlap and differ.

#2: Paying attention to time and context. Studies on meaningful work often consider meaningfulness as a stable trait, whereas a few researchers have suggested that meaningfulness could be episodic and fluctuate across a worker’s (or an athlete´s) career. This was also pointed out by many participants in one of my earliest studies. Also, in the meaningful work literature, most studies adopt an Euro-American perspective and there has been limited attention to cultural diversity in how meaningfulness develops; this is certainly true in the sports context as well.

#3: Dangers of ‘management of meaning’. Although it seems intuitive that those in positions of leadership should work towards facilitating meaningful experiences in work and sport, it can also be problematic. As Lips Wiersma and Morris (2009) point out, people already have their own sense of what is meaningful, and it would be disrespectful not to recognise that because ‘we know better’. If leaders take the ‘management of meaning’ approach, it could produce alienation if the promoted meanings do not resonate with workers’ or athletes’ own sense of meaningfulness. We discussed these dilemmas when Michael visited the Meaningful Sport podcast last year.

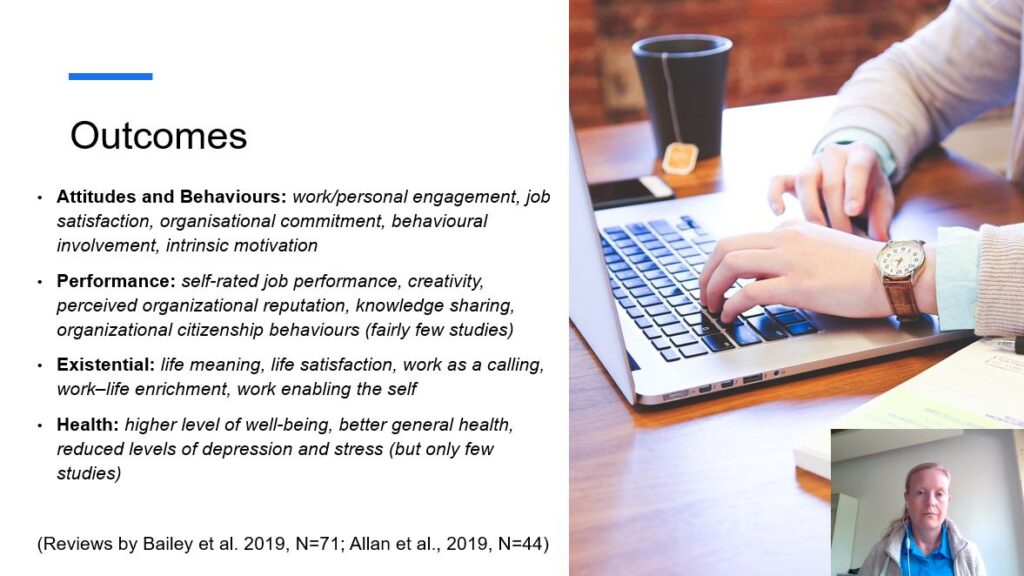

#4: The dark side of meaningful work. While the list of benefits from meaningful work is long, there is also a growing awareness of the potential dark side, such as working excess hours, loss of work-life balance, and lack of attention to other sources of meaning. Those who experience high meaningfulness in work are also more easily exploited. While meaningful work literature is slowly starting to address this dark side, sport researchers would do well to be aware of it from the early stages of our work in this area.

… And in addition to all this, the recent environmental disasters and the latest climate report remind us that our notion of meaningfulness has to address the question of sustainability of our sporting activities. Sport sector, like any other, has to seriously think about the impact we have on the planet and future lives. Perhaps the new book, Post-Growth Work: Employment and Meaningful Activities within Planetary Boundaries (now in my reading list) will help with some of this…